DAY ONE

It’s a well-known fact that there is a certain point when one becomes institutionalised, be it in boarding school, hospital or even prison.

I’ve no experience — so far — of the latter, but I’d imagine that there comes a defining moment when you’ve worked out what you need to know — who to be nice to, who to avoid, and who never to stand behind in the shower when bending down to pick up the soap.

The same certainly applies — possibly minus the soap bit — in boarding school and hospital, and for me, this institutionalisation occurs after about three days.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that this acceptance means that you can trust the guidance and received information from those in authority. No — it means that you need to be all the more sceptical of it.

And that’s precisely where I am right now.

It could probably be considered a bit extreme, getting myself admitted to a Cardiac Care Unit in order to avoid the Olympics.

When I rang my doctor for an emergency appointment on Tuesday morning, this wasn’t quite what I’d expected.

“Get yourself to A&E,” he’d said, “sounds like it needs checking out.” So that’s what I did. I’d had an uneven heart rate for a couple of months, and while it wasn’t painful or restrictive, I knew deep down that it wasn’t going to go away and would require attention sooner rather than later.

So when Tuesday’s morning run was reduced to the pace of an 80 year-old asthmatic, I knew that time had come. I’d chased the dog up and down to beach for 20 minutes, much to the amusement of every holiday-maker except for the family whose ball he’d punctured, before collapsing to my hands and knees when I’d finally managed to lasso the bastard.

The last time I’d found breathing this hard was in the Himalaya at 18,000 feet, and the discomfort I felt in the centre of my chest, a sensation suggesting that my lungs and vital organs had been squashed into an area the size of matchbox, didn’t bode well.

No amount of indigestion pills relieved the tightness and I had more than a sneaking suspicion that, while the weights I had lifted on Monday may have tightened my chest, they wouldn’t have impaired my ability to breathe in such a dramatic fashion.

This was a heart problem. Pure and simple.

Bangor A&E is about an hour’s drive away from where I’m staying, and on a quiet Tuesday morning, I’m seen in Triage in less than a minute by two nurses. When I tell them — a little dramatically perhaps — that I might have had a heart attack, they swing into action, taking bloods and wiring me up to a host of diagnostic machinery, with the precision and quiet calm of the Welsh front row dismantling their Irish opponents.

An hour later, after a protracted debate between the duty registrar who no one can understand — least of all the Welsh nurses — I’m on a bed in the Cardiac Care Unit.

Two things strike me about this ward: firstly the spectacular view of Snowdonia, and secondly, how cold it is. The air conditioning makes the place resemble a morgue and I wonder if this is, for many inmates, because the one leads on to the other.

I can’t have much blood left, but what I have is being thinned faster but considerably less pleasurably than I can usually manage with six pints of Guinness and half a bottle of Merlot.

Eventually, I’m seen by a posse of doctors, led by the Head Cardiologist. It’s a big group standing at the end of my bed; doctors trying to make clever clinical suggestions, or avoiding stupid ones; arrhythmic nurses, the ward sister, a pharmacist and a few undetermined bods who are probably on work experience or have come to visit someone, but find the goings-ons in my cubicle more interesting. If I can attract this level of a crowd at my funeral, I’ll be well impressed.

They scan my heart, do another ECG trace, stroke their chins and tut some more. The

Head Cardiologist, who I won’t name for legal reasons, is a small but hairy Eastern European gentleman with a deliberately unsophisticated grasp of the English language, and has the misfortune to both resemble and sound like a Meerkat. Mercifully though, he stops short of making that dreadful lip-sucking noise and uttering the word ‘simples’. He asks me to pump my arms as fast as I can, as though I’m angrily conducting a totally inept orchestra, which, in a sense, I may well be doing.

This has the effect of raising my heart rate from 30 to 40 but not much else; It should be significantly higher, even from this level of modest exertion. Eventually they decide to put me on a treadmill to see how high my heart rate will go under more intensive exercise.

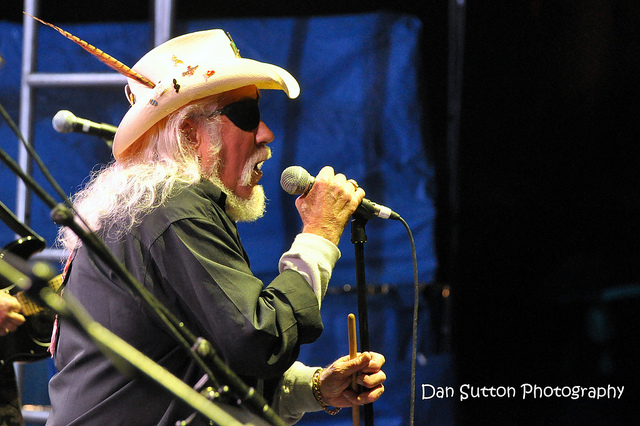

I, of course, take this as a challenge, and half an hour later I’m in a room on the ground floor, a cross between a treatment room and a basic gym. A laid back West Indian guy in his 60s, with a droopy moustache and straggly hair, who looks a bit like Clive Lloyd is controlling the test; Dr. Meerkat stands in the background making urging me on, while I’m on the treadmill going for it.

There’s a large nurse who’s in charge of monitoring my blood pressure and ensuring that I hang onto the handle and don’t contravene any Health & Safety laws, and I can’t help thinking that a bit of treadmill work would do her absolutely no harm at all.

Clive Lloyd, seated at the console with his legs crossed, humming what sounds suspiciously like a Bob Marley number, mutters something to Dr Meercat who demands that the level is increased. I’m finding the effort required to walk at this pace and incline is pretty easy, but so far my heart rate hasn’t got much above 60bpm. The incline is whacked up to 10 per and the speed to 7kph. This is now moderately hard work, but, stubbornly my heart won’t go above 80bpm and suddenly I’m sweating like the proverbial paedophile in a clown suit, on the proverbial bouncy castle.

The test, I’d been told, will last around 3-5 minutes but so far I’ve done nine, and that’s before my tormentor demands that the thing’s raised to 15 per cent. Two minutes later, I’m soaked in sweat and panting like a fat bastard in a pie chase when he finally calls a halt. We’re all a bit concerned, despite my ability to rise to the challenge, that I could only get my heart rate to top out at 100bpm.

Back on the ward, Dr Meercat explains: “You tell me have been previously been diagnosed with Stage One Heart Block… this is referred to as ‘atrial fibrillation’. Zis is now considerably vurse and whether you have total heart block — although I don’t think that you have, or you vud not have been able to conduct ze test so… you know. So we need to hmmm… ascertain.” He paused for effect and sidelong glances from admiring subordinates, who were, like me, desperately trying to take a modicum of sense from what he was saying.

“Ve vill need to re-set ze rhythm of your heart.” He adds that he must first check that no clots have formed, (and by this he isn’t referring to the ever-growing swarm of medical people crammed into my cubicle) as, if there is a clot, belting me with mega-volts of electricity will have the same effect and an avalanche — only more deadly — and will almost certainly result in a stroke, and, well… instant death.

Simples.

This procedure, which should normalise things and permit me to carry on as usual, will be done on Friday, after my blood’s been allowed to thin a bit and I’ve had plenty of time to worry about it.

At worst I could die if Dr Meercat and his cronies somehow fail to detect a potential blood clot that may be lurking in my left ventricle — or right atrium. To check for this, they will insert a camera into my gastrointestinal tractand satisfy themselves that there’s nothing sinister lurking there.

Then, with a bit of luck I’ll be twatted with a couple of gigantic metal plates with the electrical loading of around half the National Grid, and than will reset things. At best, if there’s no clot, my heart will be re-started so that the top chamber contracts in unison with the bottom one, instead of the former pushing out blood at around 35 bpm and the latter flapping around as effectively as a dying fish, twitching around 400 times per minute.

I won’t know anything about this, of course, as I will be under a general anaesthetic. So I won’t be aware of the probe, inserted through my mouth to seek out potential clots, nor the electric shock to normalise my arrhythmic heart beat. And, best of all, should they screw it up entirely and I die, I won’t know anything about that either.

DAY TWO

I’m in Bed Six from which I have an outstanding view of Snowdon and the horseshoe of mountains known as the 15 Peaks. I’ve run across these in a former life when my heart effortlessly pumped a plentiful supply of oxygen to muscles eager to cover the ground.

Below me is the helipad where the future King of Great Britain deposits casualties from the hills or the sea in his shiny new yellow RAF Sea King helicopter several times a day. At least, I fantasise this most noble of public servants dashingly rescuing his future subjects from a cold, wet death until someone points out that he’s actually at the Olympics, in his official capacity for Ok magazine, gargling his toothy admiration and praise for our wonderful athletes, seated beside Tony Cameron.

Occasionally, the red Air Ambulance competes for space on the helipad to unload those requiring urgent hospitalisation from more common-or-garden conditions, such as the 65 year-old bloke, stung by a wasp, who had been wheeled into the defibrillation suite where I lay on Tuesday morning.

I get a visit from Dr Meercat and his team after I’ve scoffed a pretty indifferent supper. He satisfies himself that nothing has changed in my condition and that I understand tomorrow’s procedure.

If this doesn’t work, they’ll try again on Tuesday and this is where my point about institutionalisation comes in — it’s only Day Two and I still really, really want to get out of here, but curiously, I know that come Saturday, if I’m still here, I’ll be past caring.

Once Dr Meercat and his posse depart, I settle down to try to pass the night.

I’ve never got much sleep in hospital since I was a baby and tonight is no exception.

There’s an emergency resuscitation in Bed Four, resulting in the occupant being evacuated, either to the morgue or to Intensive Care — I’m not sure which.

And there’s an old guy on Bed Two across the aisle from me who’s struggling as if every breath is his last and by 3am, I’m beginning to wish that it was. Eventually, I consider self-medicating myself with a cocktail of Valium and Codeine Phosphate painkillers which I’d had the aforethought to put in my pocket yesterday morning — along with my nasal spray. But then Dan, the night nurse, who slinks around with a lopsided grim on his face that reminds me a little of Norman Bates, pops his head around my curtain and I ask him for a sleeping pill.

Eventually I pass out and enjoy a deep, dreamless sleep, until he wakes me up an hour later to take my blood pressure.

DAY THREE

It’s been nil by mouth since midnight, but I’m not entirely ravenous as I left it until 11.55pm to finish off an entire bag of wine gums, a packet of dried fruit and nuts and a bar of Bourneville chocolate.

It’s 10 am and The Team arrive. I’m introduced to the anaesthetist who has marginally less of a command of English than Dr Meercat, but manages to convey to me what’s about to happen.

Dr Meercat is playing with what appears to be a large writhing adder, attempting to slide into a huge condom. This, it transpires, is the tube they’re about to insert into me. None of your micro-filament stuff here — more like Dyno Rod.

Attached to my head is what I assume is a piece of breathing apparatus, not dissimilar to those used in airplanes when the cabin de-compresses. However, it’s not actually attached to anything and, as it’s flapping around as ineffectively as my right ventricle, I question whether it’s really necessary.

Clive Lloyd plays around with it for a moment, shrugs and turns away to busy himself with something way more important.

“About as much use as a Ryanair oxygen mask,” I say, which elicits a general grunt of agreement from those present. The mask is removed.

“I hope I’m going to be well sedated for this,” I say, and with that I’m given an injection through the drip in my right arm — the one in the left arm fell out during the night, more about that later. This instantly makes me feel all woozy and really rather good about things.

“I just need your autograph here, if you’d be so kind,” says Dr Meerkat.

“And who should I make it out to?” I ask, as the euphoria of the sedative courses through my veins, “Your wife… your daughter, or just you?

“Just sign consent form, please,” he replies, humourlessly. “When you are famous author, maybe I ask for autograph, but consent to procedure for now… yes?”

I sign and that’s pretty much the last thing I remember.

I awake as the last of the snake is being removed from my throat and vomit violently into a cardboard tray held under my chin my a nurse called Sian who smiles appreciatively and wipes my nose.

“All done, you can relax now,” she says in the manner of a priest who had conducted an exorcism. I do a quick mental audit to confirm that I’m still alive, and am relieved to find that a) I have not become a homosexual, b) my ability to make people laugh at my jokes is no better than it was before, therefore I can’t be in heaven, and c) my throat hurts like hell, which sort of rules heaven out as well.

Dr Meerkat is standing over me, looking pleased.

“Vell, ve zeem to have solved ze problem,” he says, nose twitching a little. “Your heart in back in rhythm, slow beat yes… but, sinus rhythm, so you can go home soon.”

I’m feeling pretty groggy, though, and I’m not surprised to receive the news that I’m not allowed to drive for 24 hours. Bad move; I should have just packed my stuff and buggered off. Eventually it’s decided, that I should stay in another night as this will allow my warfarin levels to be checked. I accept this with the same grace that Nick Clegg accepts the fact that he will never be Prime Minister, and am wheeled next door to the Glyder ward.

Here I find a motley collection of old men who look as if they’ve been here for ever. This only enhances my sense of institutionalisation — work out who’s who, who to avoid, who to be nice to… and so on.

There’s an old guy in the corner lying on his bed in a surgical gown with an unkempt beard and the remnants of a head of curly hair. Bizarrely he’s wearing aviator sunglasses and looks like a cross between Dr Hook and a relic from the film Easy Rider. He has what appears to be an amazingly intricate series of tattoos on his legs which I’m about to compliment him on until I realise that they’re not tattoos.

Opposite him is an older man with a perfectly vein-formed roadmap on his bald head. He’s lying on his bed facing the window covered by a woollen blanket and as I enter the ward he farts noisily. Unaware or, more likely, undeterred by my presence, he puts his hand behind his bottom and wafts his gaseous release in my direction.

“Take whichever bunk you prefer,” invites matron, in the manner of the Senior officer of the Escape Committee in The Great Escape, as the smell reaches her too. “You might be better over here,” she says, wincing conspiratorially, as I dump my meagre belongings onto the bed furthest from The Farter.

There’s a fairly normal looking bloke on the far side of the ward and we exchange nods as The Farter reconnects with his environment, sits up in much the same way as Lazarus may have done, and asks me in Welsh if I’m Welsh or English.

The great thing about the Welsh language, and why I consider that I’ve almost cracked the ability to understand it, if not to actually use it as a channel of communication myself, is that there are so few words in each sentence that are actually Welsh. I would guess, at a conservative estimate, that a minimum of one word out of every four is an English word for which no Welsh translation exists; and one word out of every four is a fabricated Welsh word, made up because no Welsh word had hitherto existed. Examples of this are ‘parc busines’ (business park), ‘toiled’ (err… toilet) or — and — this one’s a bit more tricky: ‘gwasanaethau’ (services, usually on motorways or major trunk roads) which, of course, were still a long way off when Welsh was last a living language.

Now before you call me a racist or, even worse a fascist, let me say that I don’t think that this is entirely a bad thing; the Welsh language still allows the indigenous population to call a foreigner (an Englishman) a wanker with complete impunity, and the importance of that cannot be under-estimated.

“I’m Irish,” I tell The Farter, considering that this is the option which will cause the most confusion and therefore the least conversation.

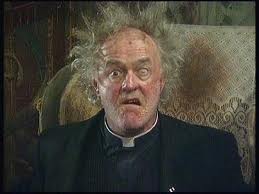

Beyond The Farter, I see there’s a fourth inmate; an elderly gentleman sitting reasonable upright in his chair until he erupts like unstable uranium, muttering to himself in the manner of Father Jack, each time his chin bangs into his chest.

But for those with the capacity of independent movement, there is much more freedom in this ward. In fact, so much so that I’m actually permitted to take the lift and descend to the ground floor where I find the cafe manned by an elderly zealot with such a passion for protocol that it takes almost 20 minutes to obtain a cup of tea. Still, it passes the time.

Seated outside in a sunny courtyard, I relax and begin to nod off until I’m roused by a procession of wheelchair users trying to get through the chain-link curtain that separates the cafe from the courtyard, whose tendrils keep getting caught in their wheels. This door adornment serves absolutely no purpose other than to make it difficult for able-bodied people, and a near impossibility for wheelchair users, to access one area from the other.

But my earlier post-zapping euphoria has abated and I notice that I’m feeling pretty rough. My left arm, from which the ineffective drip had been removed this morning, is hot and puffy, my head’s pounding and I feel as if I’d got ‘flu. Wound infection, I conclude, correctly self-diagnosing the symptoms, and make my way back to the ward.

I point this out to matron and within minutes the little registrar who had caused all the confusion in the defibrillation ward two days ago, appears at the end of my bed. I groan loudly which just about drowns out The Farter’s latest release and Father Jack’s mutterings.

I tell him that I have an infection in my left arm caused by a drip which was incorrectly inserted, and he smiles and nods his head.

There’s not much doubt about the infection as matron has already registered my high temperature, and the swelling and heat from my arm should be enough to confirm — even to a first year medical student — such as the idiot who put the thing in — that this needs treatment.

Moreover, I point out to him that, as a perfectly adequate drip has been left in my right arm — for reasons which are not immediately apparent — the way to go would be to whack the infection with a strong antibiotic straight into the vein. But this plan doesn’t appeal to him and instead I’m given a pill containing penicillin while, bizarrely, the drip is left in my arm.

Now this is really the point of all of all of this, and why I may well eventually write a book called “Surviving Hospital” to pass on the wisdom I have accumulated over many years from admissions to a catalogue of hospitals in a host of different parts of the world. There is a commonality that applies to all my experiences from Bangor to Kathmandu.

And I will probably write this when incarcerated in hospital as there are few better places to write a book; prison perhaps…

My first piece of advice to the unwary would concern the mental condition I refer to as ‘institutionalism’. It happens to everybody; it happened to me on Day Three at precisely 12.15pm, the moment when I accepted that my stay would be extended.

It will happen to you if you find yourself in hospital one minute, one hour or one day longer than you had been told you will be in for. Because this is an eventually that you hadn’t been expected or mentally prepared for.

The precise moment at which institutionalism occurs coincides exactly with your condition being downgraded. It’s a bit like a platoon of Germans leaping from a hedge in Northern France in 1944 yelling: “Hände-hoch! For you, Tommy ze var in over!” Except, if course, it isn’t over; you’ve merely joined the escape committee.

Surveying my fellow-inmates, I see that, for them, institutionalism has long-since set in. And with this acceptance of my extended stay, dawns this realisation that I am here, not because I’m an observer but because I am as much a part of the process of physical decline as any of them, and this brings with it a certain sadness.

For my second piece of advice, I would recommend to check, check and check again. Never assume that a nurse, doctor or senior consultant has the slightest idea what they are talking about, especially when it comes to medication.

And this becomes more critical as your condition becomes less critical.

It’s 7.30 on Day Three and Sarah, the duty nurse, who looks about 16, has come to give me my medication. All goes well until she goes to inject an anti-coagulant into my stomach. Now, to be fair, I’d been having these extremely painful injections night and morning for the past three days to reduce the risk of clots forming in my heart. But this was so that the electro-zapping procedure could be carried out, and, as I point out to Sarah, this has now been done. If I’d had someone to collect me I’d be home by now, where I certainly wouldn’t be having a needle thrust into my gut.

“Well, you haven’t been signed off,” she says, advancing on me with a syringe.

Eventually I manage to get her to check with the Cardiac Care nurses, who confirm that I don’t have to have it if I don’t want to. In fact, I don’t actually need it.

I’d had a similar situation in Kathmandu a few years back. Still suffering from the effects of sedation after an emergency knee operation, I was given three lots of antibiotics in an hour then none for two days. You learn.

And my final piece of imparted wisdom, for now, is this — make some friends; you never know when you may need them.

If you plan — and most of us do — to live in relative comfort to a reasonable age, before all avenues of pleasurable activities have been curtailed one way or the other, then you will need a social network, particularly at times like these. And by social network, I’m not referring to Faceache or Twatter. Real people; you need real, physical, get-off-your-arse people.

And if you’re a bit like me and have spent most of your life either avoiding forming friendships or actually pissing people off and only have two friends — one who lives in Ireland and the other who lives at the other end of England — then you are going to be stuck with something worse, much worse that isolation and loneliness.

Hospital food.

It’s impossible to adequately describe how bad hospital food is. The fact that a slice of bread (stale, they should add) appears as a menu option is indicative of the thought and level of preparation that goes into providing appropriate nourishment for ill people. The overriding assumption behind the provision of hospital food is that, because you’re ill, you can’t chew; always has been — always will be. And not only that, meals for an entire hospital are cooked on one small Camping Gaz stove.

Now in certain parts of the world — well, the Third World, although I believe we’re supposed to call it the Developing World now, although I’m buggered if I’ve noticed much in the way of development — hospitals do not provide food; nor water. It is the responsibility of relatives and friends to feed their loved ones.

And that, I believe, is the way forward, and why it is essential — however hard the process — to develop a network of people who care enough about you to deliver a regular supply of food parcels to replace the unappetising pigs’ swill that appears on your tray three times a day.

DAY FOUR

It’s 6.30 on Saturday morning and the day has not got off to a good start.

What I would describe as a camp orderly, wearing green overalls, with a ‘skinhead’ hairdo approaches me and demands blood.

“You are…? I ask suspiciously.

“I’m Gareth, I’m a ward assistant,” he replies cheerfully, “I’ve been taking blood for months now, and I’m pretty good at it… really.”

No, I think, Gareth, your job is to sweep the floor, deliver the right meal to the right bed and to change the sheets. Nothing wrong with that — not your fault — but if you wanted to be a nurse or a doctor, or even somebody who’s qualified to take blood, you should have worked a bit harder at school. I mean, trolly-dollies don’t land commercial airliners, do they? Not even on Ryanair.

“Would you prefer a nurse to do it?” he asks, mentally figuring which nurse would be the most annoyed to have this added to their existing workload.

“If you don’t mind, Gareth,” I reply, “Sorry, but yes… I would. I’m a bit squeamish, I’m afraid.”

He shrugs and returns a couple of minutes later with the Camp Commandant, a mean-eyed 6’2″ 18 stone seething mass of barely-female shot-putting nurse by the name of Jenny, who clearly resents the diversion.

“Right — left arm please,” she demands, with an “I’ll give you squeamish… let’s put an end to this nonsense,” attitude.

“Ah… that one’s infected,” I reply, “and would you mind pulling the curtain round?” I really don’t like having blood taken and I don’t particularly want Father Jack or Dr Hook to share my discomfort; The Farter has his back to me, as usual, which is a mixed blessing.

“Well, if I do, he’ll have to stay in the cubicle,” she replied, nodding in Gareth’s direction.

“Why?” I ask.

“Chaperone. You’re male, I’m female”.

“Really? As if… in your wildest dreams… you’d consider… it to be even the remotest of

possibilities, that with a serious infection in my arm and in a post-operative stupour, I would actually try to jump you, as you take blood from my one good arm…? I mean, even if you were ten stone lighter and vaguely attractive? Do me a favour! Actually, in all honesty, I’d rather have woken up from the general anaesthetic as a homosexual…”

… Of course, I think this, I don’t actually say it. Although, to be honest, I’m still a but hazy on exactly what was said, so I may well have done.

And so that’s where I am now; waiting for the results of the blood tests. If my IMR, or whatever it is, is within the right parameters, and the antibiotics are vanquishing the blood infection, then I’m free to go.

But for some reason, the opening bars of Hotel California keep drifting into my mind… and of course, Glen Frey’s immortal lyric: “You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave…”

POST SCRIPT…

This article has already provoked a huge amount of comment, mainly critical, and I suppose the sensible thing to do would be to take it down.

However, It was written as a ‘light-touch’ piece with the intention of entertaining rather than ridiculing or causing offence.

I would like to make it clear that the attention I received from the medical and ancillary staff during my stay in Bangor hospital was exemplary. I found them utterly professional, diligent and humane, and in an age when NHS professionals come under fire for a lack of connection with patients, I could have expected nothing better.

The characters in this piece are entirely fictitious and bear no likeness to any of the staff at Bangor Hospital; no Meerkats were either hurt nor insulted in the writing of this piece, and Clive Lloyd has probably never visited the place either.

There is a male nurse who works the night shift; his name is not Ben, and he doesn’t look a bit like Norman Bates. Neither is there an 18 stone shot-putting nurse called Jenny — at least if there is, I didn’t come across her — thank God.

I profusely apologise if my piece caused offence to any homosexuals (I have no problem with you, guys — I just don’t want to be one myself, that’s all).

I know that our noble leader is called David and not Tony, but can you really tell the difference?

The one real piece of offence I may have caused is to state that Welsh is not a living language. I’m sorry, but I do stand by this because a) it no longer evolves as a language in any organic way, b) it is not the first language of the majority of the population, and c) it continues to be taught in schools for the primary function of pissing the English off — absolutely nothing wrong with this.

And finally, I’m sorry if you work in the catering department of Bangor Hospital… yes, the food was so bad that mere words cannot adequately describe it.